10 Women In Science You Should Know

Barbara McClintock

Plants have an ability to communicate, Barbara McClintock (1902-1992) believed, and she listened. She became one of the most influential biologists of the 20th century—even though she voluntarily declined to publish some of her seminal work in the 1950s because of the skepticism of mainstream geneticists. Born in Connecticut, McClintock attended Cornell University, where she began to study maize (corn) plants. In the course of her research on maize, much of it at Cold Spring Harbor Lab, she divined the way that genes can be controlled and suppressed. She also discovered that pieces of DNA can move around during reproduction. This form of recombination, known informally as “jumping genes,” occurs in humans, too. When McClintock received a Nobel Prize in 1983 for her insights, she told the New York Times it seemed unfair to receive an award “for having so much pleasure over the years, asking the maize plant to solve specific problems, and then watching its responses.”

Ynes Mexia

Ynes Mexia (1870-1938) took neither a traditional nor smooth path to scientific excellence. She initially planned to become a nun, endured two short, ill-fated marriages, and did social work in San Francisco before matriculating, at age 51, at the University of California, Berkeley. When she died 17 years later, she had become one of the most intrepid and accomplished botanists in North America. In her short but prodigious career, she collected an estimated 150,000 plant specimens in the western United States, Mexico, Alaska, and South America. An indomitable researcher who traveled far and wide to collect plants, she gave “lantern-slide lectures” about trips up the Amazon and along the Equator. The discovery of the genus Mexianthus is attributed to her.

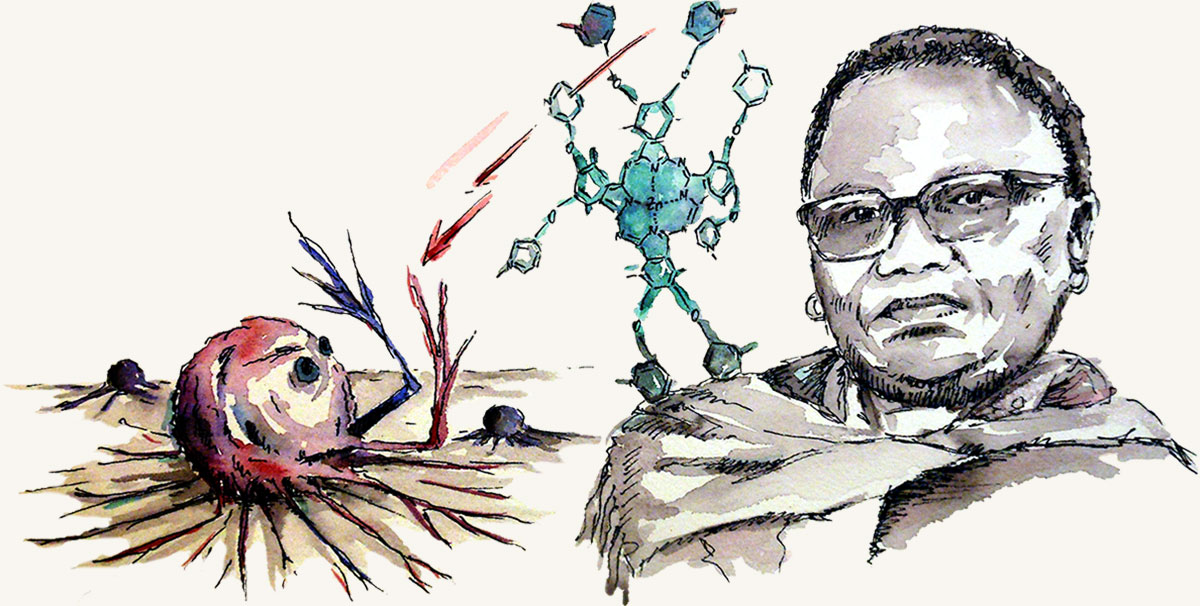

Tebello Nyokong

When Tebello Nyokong (1951-) was growing up in the mountains near Lesotho, South Africa, she only went to school every other day. She spent the rest of the week tending her family’s sheep. It was among the grazing sheep, she says, that she first became a scientist: listening to the sounds of the field, observing birds, identifying edible plants. Though she was told endlessly that “women do not need a career, they just need to marry well,” she eventually went to university, and then to graduate school at the University of Western Ontario. She returned to South Africa to become a highly respected and prolific professor of chemistry at Rhodes University. Among many other accolades, she has won the L’Oreal-UNESCO Award and the Order of Mapungubwe, South Africa’s highest honor. Her extensive work in nanotechnology includes a special dye which, while generally non-toxic, reacts to laser light by spitting out a deadly form of oxygen. Such compounds promise to revolutionize cancer treatment, allowing doctors of target cancer cells without harming healthy tissues.

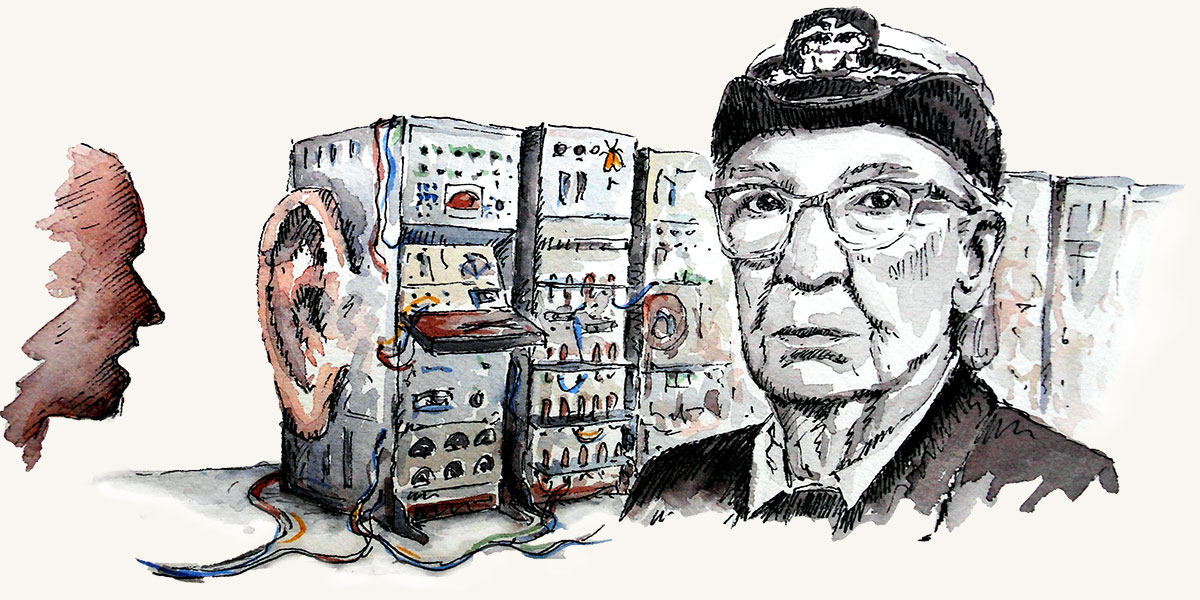

Grace Hopper

Grace Hopper (1906-1992) became one of the world’s first computer scientists because of Pearl Harbor. After the attack, she left a professorship at Vassar College’s math department to join the Navy. Or the Navy reserve: she was deemed too skinny for the Navy (and, at age 35, too old). While enlisted, she was one of the first to program the Harvard Mark I, the United States’ first computer. Soon after, Hopper went to work developing the UNIVAC I, the first commercial computer. It was there that she proposed that humans should be able to communicate with computers in English — not the machine’s language of 0s and 1s. Though initially controversial, this idea now forms the basis of the “high-level” languages most programmers use today. Unconventional thought was Hopper’s scientific philosophy. “[People] love to say `we’ve always done it that way,’ ” she noted. “I try to fight that. That’s why I have a clock on my wall that runs counter-clockwise.”

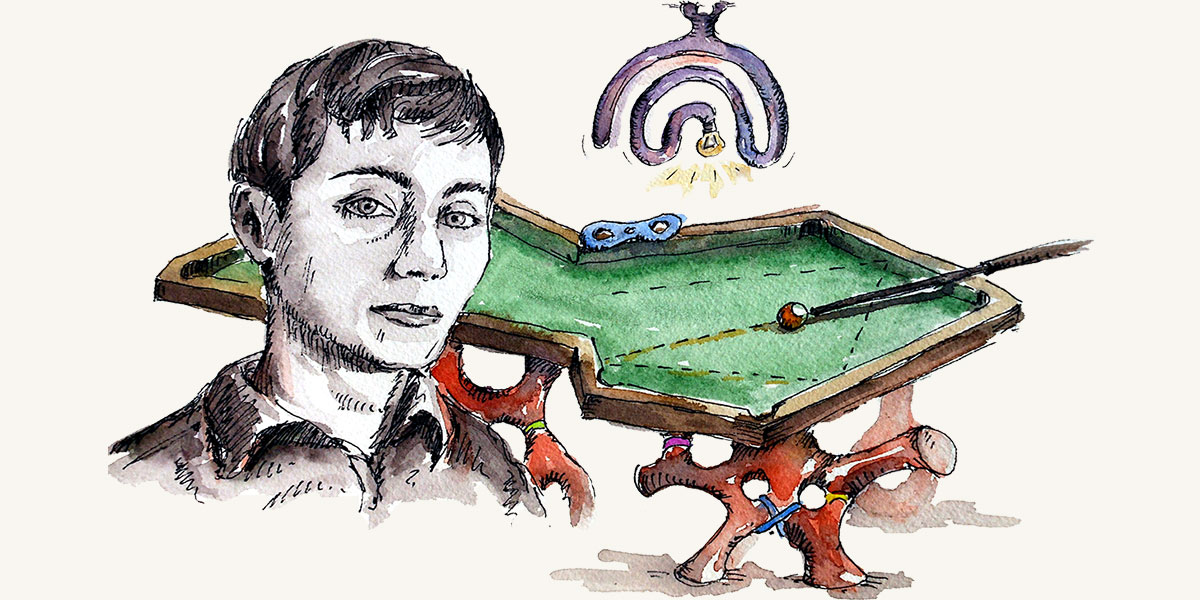

Maryam Mirzakhani

Maryam Mirzakhani (1977-2017) described herself as a “slow” mathematician, wending her way through proofs like an explorer “lost in a jungle and trying to use all of the knowledge [she] could gather to find [her] way out.” Find her way she did: the first woman to win the Fields Medal (the ‘Math Nobel’), Mirzakhani made groundbreaking advances in the mysterious interplay between geometry and chaos. She was fascinated by the mathematics of billiards, and worked on understanding how the trajectories of billiard balls would differ if they rolled and ricocheted on pentagonal or hexagonal tables instead of the rectangular tables at your local bar. Mirzakhani’s discoveries promise to shed light on conundrums in physics, engineering, and cryptography.

Born in Iran, Mirzakhani moved to the U.S. for her Ph.D. at Harvard. She became a professor at Stanford in 2009.

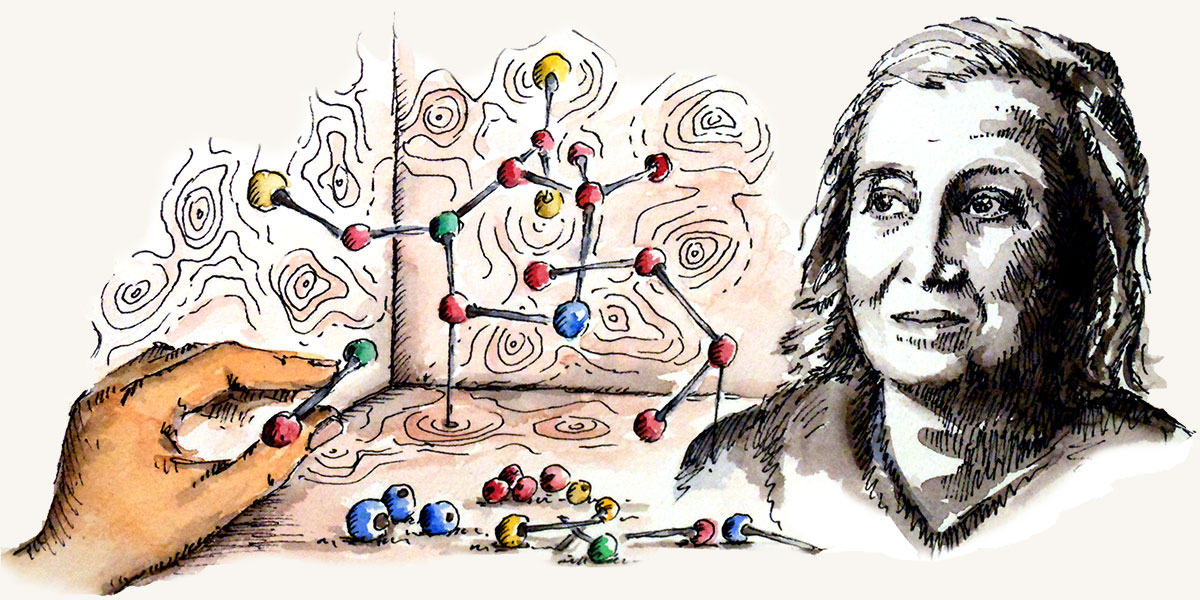

Dorothy Hodgkin

Fascinated by childhood experiments with crystals, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1910-1994) went on to do pioneering studies in x-ray crystallography that revealed the intimate atomic structures of important biological molecules like insulin, penicillin, and Vitamin B-12. Born in Cairo and raised partially in the Sudan, Hodgkin considered a career in archaeology before committing to chemistry. But success did not come easy. After graduating from Oxford, she could not find work until the legendary biologist (and outspoken Communist) J.D. Bernal welcomed her to the University of Cambridge, where she obtained her Ph.D. Returning to Oxford in 1934, Hodgkin went on to do groundbreaking research in structural biology. During the McCarthy era in the 1950s, Hodgkin was denied entry into the U.S. because of her association with Bernal; barely a decade later, her work on the structure of biologically significant molecules won her admission to the most exclusive society of all: winners of the Nobel Prize.

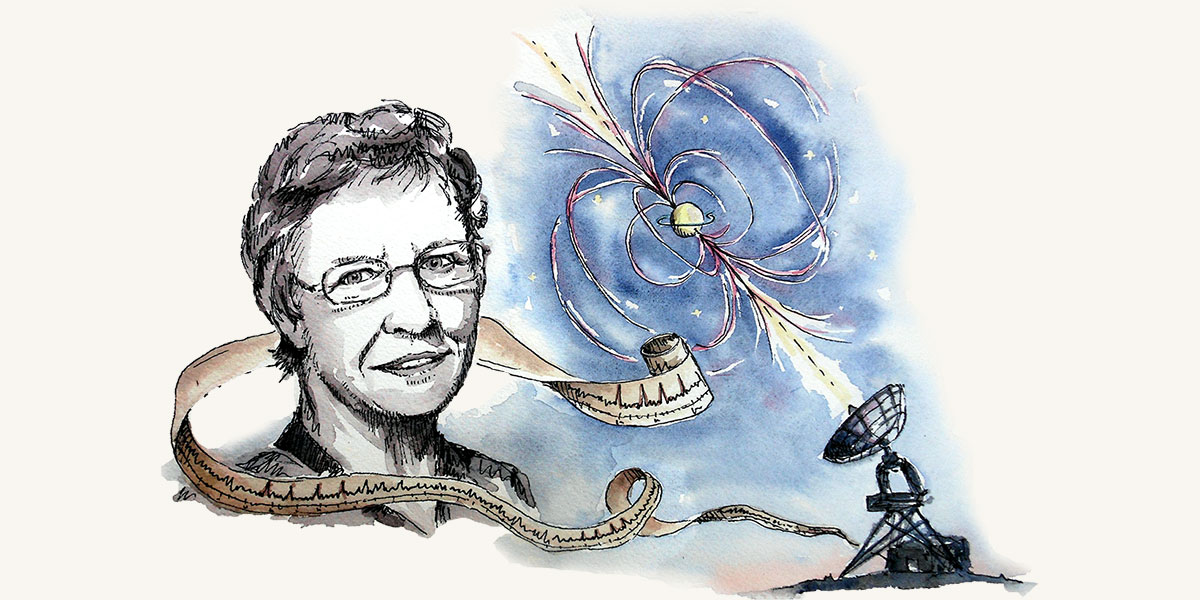

Jocelyn Bell Burnell

In 1967, Jocelyn Bell Burnell (1943-) was a Ph.D. student at the University of Cambridge when, with astronomer Antony Hewish, she discovered mysterious signals collected by radio telescopes. She realized that the signals were radio pulses emitted by a dense, spinning, and otherwise invisible star. Now known as pulsars, these stars opened up astronomy to a previously invisible and violent “radio universe.” Although she was overlooked for a Nobel Prize when Hewish shared the award in 1974, Bell Burnell received a Breakthrough Prize for her work in 2018. She plans to use the $3 million award to create scholarships for Ph.D. students, explaining to Nature, “I did my most important work as a student.”

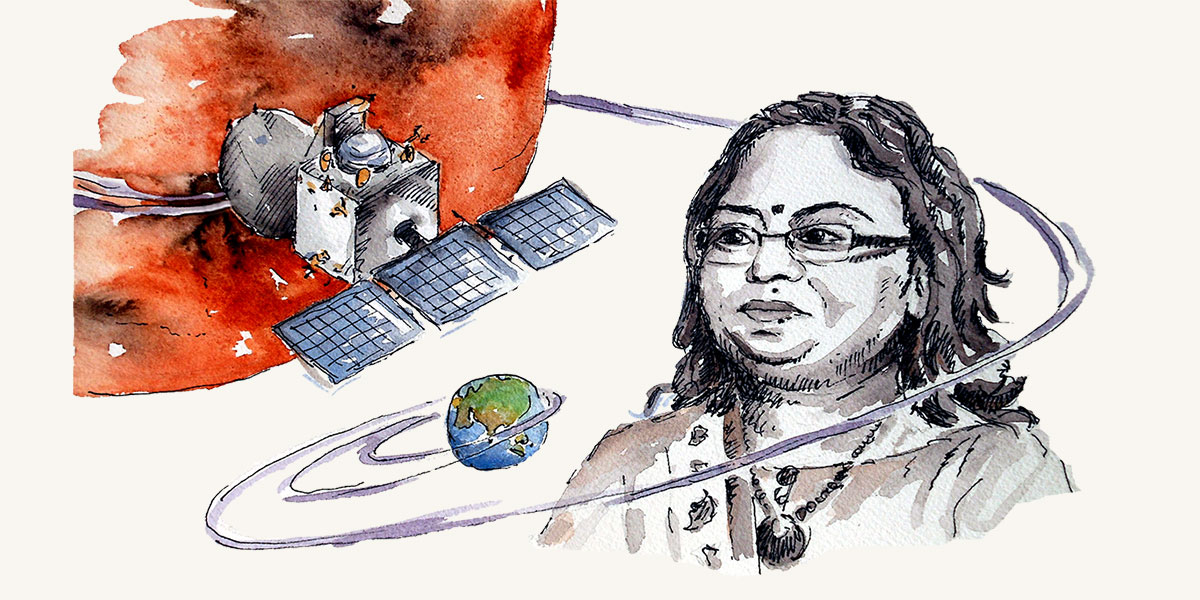

Ritu Karidhal

Known as one of India’s “Rocket Women,” Ritu Karidhal belonged to the team of scientists that guided an unmanned spacecraft into orbit around Mars in 2014— making India only the fourth nation on Earth to reach Mars. Karidhal oversaw the creation of an autonomous software system for the Mangalyaan space probe, which allowed the vehicle to maneuver on its own without having to wait for radio-transmitted directions from Earth. Born in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh to a middle-class family, Karidhal translated her childhood fascination with the moon and stars into an advanced degree in aerospace engineering from the Inland Institute of Science. The image of Karidhal and the other “Rocket Women” celebrating the successful mission—wearing saris and bedecked in flowers—went viral as a symbol of extraordinary scientists… who happened to be women.

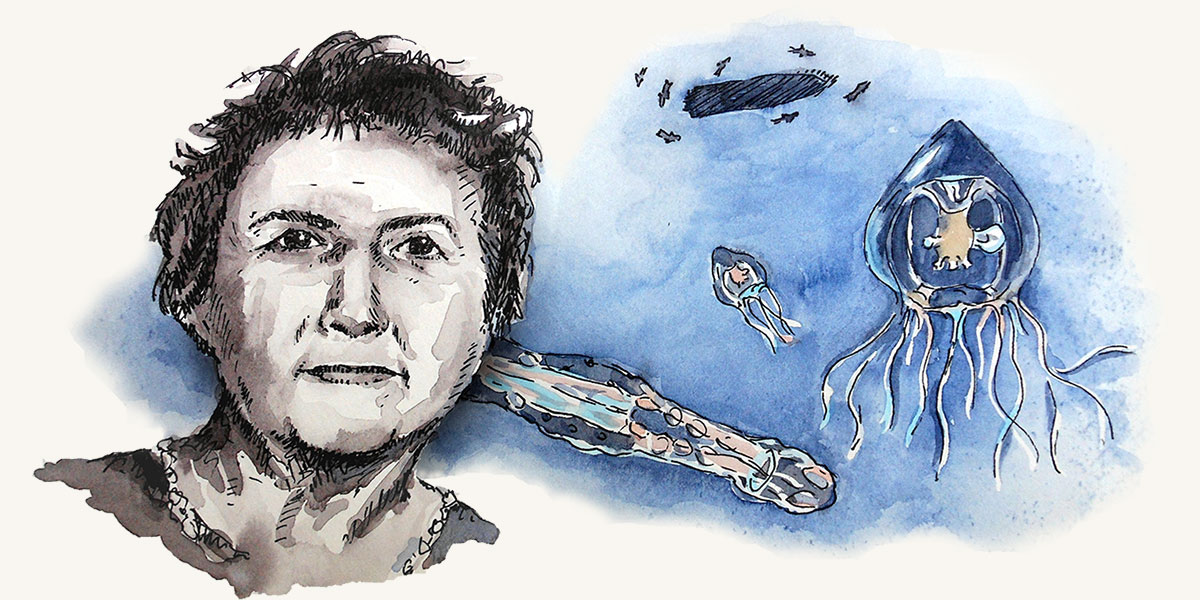

María Ángeles Alvariño

María de los Ángeles Alvariño González (1916-2005) submitted two bachelor’s dissertations in 1933: one about social insects, the other about women in Don Quixote. The distinction between science and humanities was immaterial, she said, “creativity and imagination [being] the basic ingredients” for science as they are for art. She applied her creativity most intensely to zooplankton, tiny aquatic organisms she first encountered in 1953, while on a fellowship to England’s Marine Biological Laboratory from her native Spain. Though they were little-studied at the time, we now know that zooplankton form an essential part of the marine food chain, nourishing larger animals like coral and jellyfish. Ángeles Alvariño studied the types and quantities of these tiny creatures to understand ocean currents, the movement of ships, and the effect of pollution on the seas. She discovered twenty-two new species of zooplankton, and studied oceans ranging from the Mediterranean to the Antarctic. Two species of zooplankton now bear her name.

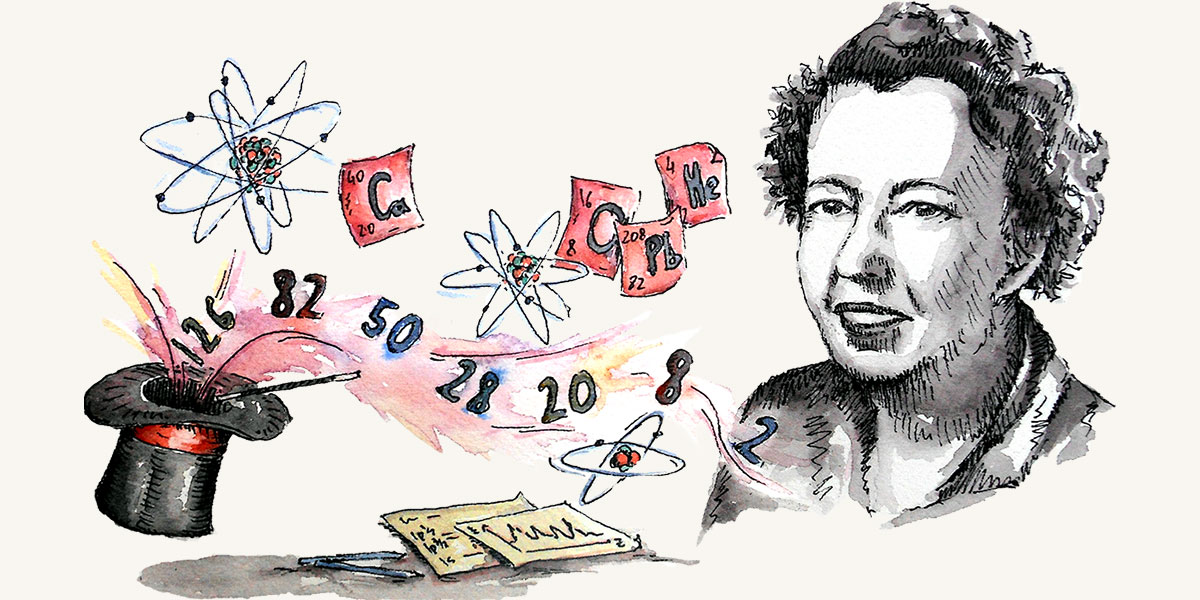

Maria Goeppert-Mayer

In 1963, Maria Goeppert-Mayer (1906-1972) became the second women to win the Physics Nobel Prize, just three years after she finally became a professor (at the University of California, San Diego).

When she enrolled at the University of Goettingen in 1924, she planned to become a math teacher at a girls’ school. But, caught up in the buzz around quantum mechanics, she soon switched to physics. After receiving her Ph.D. in 1930, she married an American visiting scientist, Joseph Mayer, and moved to the States.

Fascinated by the atomic nucleus, she spent her life puzzling out its structure. Among her greatest insights was the fact that protons and neutrons inside the atomic nucleus conform to a ‘shell model’ — much like the electrons in orbit around it. Goeppert-Mayer produced many of her extraordinary scientific achievements — including her Nobel-winning paper — while working in unpaid positions at the universities that employed her husband.

About the project

Women have been making dramatic scientific discoveries for millennia — even if they haven’t always gotten the credit they deserve. This series of illustrations by Angelika Manhart pays tribute to women pursuing a passion for science. There are Nobel-laureates from 30 years ago and innovators making waves today; biologists, chemists, physicists, computer scientists, and mathematicians; women who always knew they wanted to be scientists, and women who started grad school at 51; women from India and South Africa and North America and Iran. Eclectic by design, our list aims to reflects the many different ways to be a woman scientist.

About the illustrator

An accomplished woman in science herself, Angelika Manhart is a postdoctoral researcher at Imperial College, UK. She uses math to understand a variety of biological systems, from human muscles to bacterial swarms. Born and raised in Vienna, Austria, Angelika has been drawing since she was a child. In addition to sketching just for fun, she has worked on several projects — like the ACCESS 2017 exhibit at the New York Hall of Science, and our “10 Women In Science You Should Know” series — that bring art and science together.