Sex, Lies, and Women

Review by Elizabeth Harris

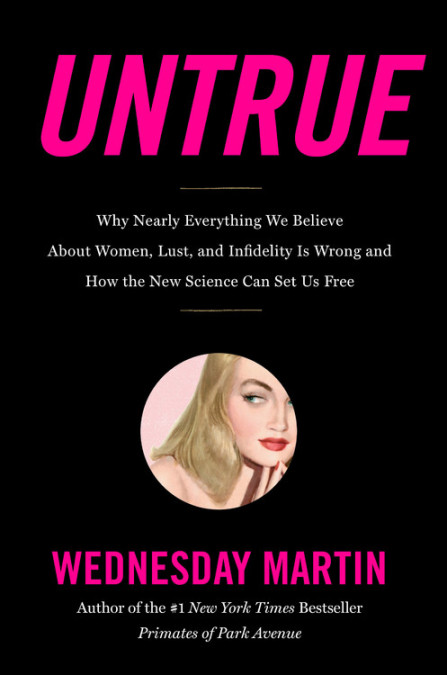

Untrue

Why Nearly Everything We Believe About Women, Lust, and Infidelity Is Wrong and How the New Science Can Set Us Free

Book by Wednesday Martin

The home features a grand fireplace, a jacuzzi on the terrace and a beautiful view of the New York City skyline. Inside, couples get intimate on the sofas. In the bedroom: a group of naked strangers. The dim light lingers on bare skin and the air is filled will low laughs and moans. For one night, high-powered executives and lawyers take off their suits and relax. Tonight, the party-goers are free to explore themselves and each other. Every single one of them is a woman.

These “Skirt Club” sex parties happen in major cities all over the world. The gatherings are the opposite of what one might expect from a “typical” sex party. They take place in glamorous venues instead of dingy backrooms. They are invitation-only. And, most unusual, they are women-only, focusing solely on female gratification. If you are surprised by this shameless celebration of female sexuality, you’re not alone — at least according to Wednesday Martin’s Untrue: Why Nearly Everything We Believe About Women, Lust, and Infidelity Is Wrong and How the New Science Can Set Us Free.

Society, Martin writes, views women as inherently less sexual than their male counterparts. In 1600s Massachusetts, married men sleeping with single women were charged with “fornication,” while married women who had sex with a single man were charged with the much harsher crime of adultery. Much has changed in the past 400 years, but gender bias still infects our assumptions about sexual appetite, and how we think about and punish adultery. A man who cheats is a Casanova, a woman who cheats is a Jezebel.

In her risqué new book, Martin addresses and challenges these centuries-old tropes. Many of us believe that men cheat more than women, and that they do so because they have a bigger sex drive. But research by Dr. Meredith Chivers (whom Martin interviews) suggests that women are just as attracted to novel sexual partners as men. According to Martin, the misconceptions arise from the norms baked into modern Western society. Martin dares to suggest that “[p]art of female sexuality, part of its legacy and its present and its future is that it is assertive, pleasure centered, and selfish.”

Martin has a Ph.D. in comparative literature and cultural studies, and frequently writes about gender, sex, and motherhood for the New York Times, The Atlantic and Psychology Today. Her straightforward and unflinching prose is not only welcome but necessary when tackling the controversial topic of female adultery and sexuality.

In Untrue, Martin approaches a series of socially contentious questions through sociological, personal and evolutionary lenses. Her goal is to provide evidence that women cheat and that many of them do so because they are motivated purely by sex. She tackles many related issues: Who are the women who cheat? How does society react to such transgressions? And what does all of this say about gender bias today? She addresses these questions with research, history, and interviews, seeking to prove that some women are just as sexually active, drawn to non-monogamy, and likely to cheat as men.

Although not always convincing, Untrue‘s scope is truly ambitious — and entertaining.

In one of several interviews featured, Martin talks to her friend Tim, whose wife is married to him, but also to another man. The three of them have a unique living situation: Tim is in the master bedroom and the second husband is in the guest room; Tim takes care of the children and the second husband, a chef, takes care of the cooking. Not only are such voyeuristic interviews fascinating, they lend support to one of Untrue’s key claims: monogamy and sexual fidelity are not for all women. Martin also interviews several adulteresses. Some of them express regret; some don’t. She presents the interviews as evidence that some women are drawn to non-monogamous relationships.

Martin also delves into the gender ramifications of the earliest ‘tech’ revolutions: the move from farming with hoes to oxen-powered ploughs, which moved women from active involvement in food production to primarily domestic roles. This shifted the gender hierarchy to favor men, which Martin uses, in turn, to explain the history of gender biases in society. She speaks with researchers studying sexual activity in bonobo chimps, with some finding that “monogamous” female bonobos actually engage in copulation with multiple partners– which she again interprets as suggesting that monogamous relationships may be unnatural.

Martin’s writing is clever and vivid. Candid discussions about sex are like “newly discovered creatures who inhabit the deepest parts of the ocean, perfectly suited and inherently appropriate to its indigenous darkness.” Similarly, when describing Angus Bateman’s famous and apparently unreplicable Drosophila study –which found that male fertility benefitted from multiple copulations, while female fertility did not– she notes “Bateman’s ideas would be periodically reactivated like a virus by anxiety about social change” and that it was “popular, popularized, politicized and sometimes populist.”

If there is a place where Untrue falters, it is when Martin reports scientific evidence. She presents a handful of studies that support her assertions with limited discussion or even acknowledgement of conflicting findings. To her credit, she admits this in the book’s introduction, stating that though “there are other studies that argue otherwise,” she is “only your guide to [her] view—informed by the social science and science to which [she] was drawn and to which [she] was referred by experts.” For me as a scientist, this raised a red flag. In science, especially in subjects like psychology and sociology, for every positive finding, there is often a negative finding. When Martin cites a study that finds support for women being more sexual, I wonder how many studies found the opposite and which evidence is objectively stronger. If you want to find the truth, you can’t just pick the studies that suit your narrative.

Martin also seems to conflate non-monogamy with infidelity throughout Untrue. When discussing female primate sexual vocalizations, Martin writes “[s]till other researchers see our very cries of pleasure as proof that when it comes to being untrue, females were ever thus.” But humans are not monkeys, and having multiple partners is not necessarily cheating: the difference lies in the ethics of having multiple partners with or without the knowledge and consent of your romantic partner. It is these ethical considerations which differentiate infidelity from non-monogamy that Martin rarely addresses. Evidence that some women enjoy non-monogamous relationships is not evidence that some women cheat. At times, Martin even comes close to crossing the line between explaining and excusing infidelity, leaving me confused as to the book’s goal and further reducing her credibility.

Still, if we give Martin the benefit of the doubt, “several decades after the great second wave of feminism… women are, as sociologists like to put it, closing the infidelity gap.” Why, then, do these “untrue” beliefs still exist? Because “we’re just not talking about it,” says Martin. “At least not in a voice above a whisper.”

As Martin puts it, Untrue is “a book with a point of view.” It will make you angry — in agreement with Martin, disagreement, or a mishmash of the two. It certainly sparked a heated debate amongst my friends, and left me rethinking some of my beliefs. I’m more aware of, and frustrated by, the prevailing narrative of the “rare” women who stray being evil seductresses.

If conversations about female infidelity up to this point have been whispers, this book is the shout we need to fill the gap in the conversation.

Elizabeth Harris is Ph.D. student in Social Psychology at NYU. She can either be found in her office studying the effects of group identity on cognition, or at the Women’s March, studying the effects of group identity on herself.