Who is to blame for climate change denial?

Review by John Dodson

Publisher

W. W. Norton and Company

Year

2019

Pages

272 pages

List Price

$26.95

Links

Amazon, IndieBound

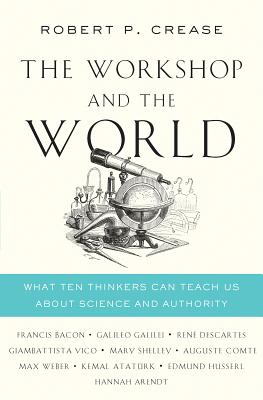

The Workshop and the World

What Ten Science Thinkers Can Teach Us about Science and Authority

Book by Robert P. Crease

On March 28 2014, the future president of the United States said the following on Twitter:

“Healthy young child goes to doctor, gets pumped with massive shot of many vaccines, doesn’t feel good and changes – AUTISM. Many such cases!”

While Donald Trump eventually encouraged vaccinations in light of the largest U.S. measles outbreak in the past 25 years, this followed months of presidential silence on the matter.

It’s clear to anyone paying attention in 2019 that science denial extends to the Oval Office. President Trump has repeatedly doubted scientific consensus ranging from climate change to whether regular exercise is good for your health. Millions of Americans hold similar views.

How did we get here? In The Workshop and the World: What Ten Thinkers Can Teach Us About Science And Authority, Robert P. Crease traces scientific authority (and science denial) from Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis in the early 17th century to Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition in the second half of the 20th. Through the prism of the scientific workshop, defined as “a coordinated ongoing interdisciplinary network of scientists,” Crease, chairman of the philosophy department at Stony Brook University, chronicles the lives of ten thinkers on scientific authority and how they shaped contemporary views.

The book’s central premise is that the scientific workshop, the collective process of acquiring and fine-tuning new knowledge, is an instrument that promotes progress but may also undermine science’s own authority – for example, through overselling the benefits of science or failing to appreciate its risks. One example of the latter is embodied in Victor Frankenstein’s homicidal monster, envisioned by the novelist Mary Shelley, which seems especially relevant in our modern era of artificial intelligence and human genetic engineering. Another is Hannah Arendt’s concept of “world alienation” in which technological progress detaches humans from their immediate earthly surroundings and therefore inhibits participation in the public sphere. This example again resonates in our current era of smartphone addiction and political cynicism.

The book begins with an anecdote. Standing on the Mer de Glace, the longest glacier in France, Crease encounters a series of signposts. The highest post, “Level of the glacier, 1820,” now stands amid pine trees and rocks. He then descends 2,000 vertical feet before reaching the final post: “Level of the glacier, 2015.” By 2019, the glacier had already receded from its 2015 level. A workshop of scientific authorities – glaciologists, chemists, physicists, engineers, and climatologists – have determined that “Mer de Glace and other glaciers will go on melting; many will vanish entirely,” Crease writes, yet many politicians still question the very existence of climate change.

Science deniers like Trump or Senator James Inhofe – who famously brought a snowball into Congress to question the science behind climate change – operate by “rejecting the authority of the workshop.” While they still listen to engineers when building bridges, and still go to the doctor for medical advice, science deniers also take advantage of science’s inherent weakness: that it “can be used to promote hidden agendas, is abstract, and is uncertain.” This strategy of denial has real-world consequences – to which anyone who lives in coastal communities affected by climate change, or whose family is put at risk by unvaccinated children, can attest.

In addition to his academic career, Crease is a popular science writer whose prior books include The Quantum Moment and The Great Equations. His prose is accessible to a wide audience (including non-scientists), and he is generally effective at distilling complex philosophical treatises (for example, Giambattista Vico’s The New Science) for the casual reader.

One minor flaw in this ambitious text is that Crease focuses on individuals, which seems an inherent contradiction in a book about networks of scientists working together. More description of the supporting cast members (other scientists) who formed the physical “workshop” throughout history would have been helpful. Still, Crease manages to distill several centuries of scientific thought for a broad audience.

What can we do to mitigate science denial? Crease ends the book with specific short-term and long-term tactics, including having politicians take a pledge to let their decision-making be guided by scientific facts, using comedy to expose hypocrisy, prosecuting science deniers for endangering public health, and asking scientists to step outside their own workshop and engage with the larger world. Some of these prescriptions may be overly ambitious (will politicians really pledge to “defend and maintain the scientific infrastructure of the country”)? But when so much is at stake – ranging from human health to the fate of the planet – Crease’s ambition seems both warranted and timely.

John Dodson is an Assistant Professor of Medicine and Population Health at New York University School of Medicine.