The Roommates You Hate… But Can’t Live Without

Review by Tanvi Butola

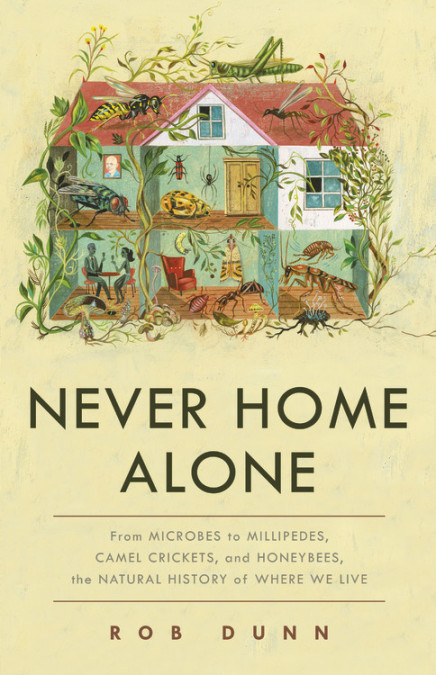

Never Home Alone

From Microbes to Millipedes, Camel Crickets, and Honeybees, the Natural History of Where We Live

Book by Rob Dunn

We live in the Antibacterial Era. We line our walls with Purell dispensers. We obsessively clean surfaces with disinfectant wipes. We send our children out into the world with tiny hand-sanitizer bottles hanging from their backpacks. No sooner do they touch a park bench than their hands are doused in a “life saving” product that kills “99.99% of germs.” Does it really?

Never Home Alone is a cautionary tale about how we try to dust, scrub and disinfect all other living things out of our lives — to no avail and to our detriment. “What clean has never meant, and will never mean, is sterile,” writes author Rob Dunn, “but that’s okay.” We share our homes with some 200,000 species. Out of 80,000 bacterial species, only about 100 pose a potential threat to us. Terrified of a few hundred, we indiscriminately try to eradicate all the rest, including many microscopic allies fighting against our pathogenic enemies.

The bigger question here is why we want to eliminate all life around us. Is it because scientists fail to communicate the distinction between the harmful demons and benevolent angels of the microscopic world? Is it because people fail to see that we need to save the angels to fight the demons? Is it because industry successfully feeds on people’s fear of the hundred-odd demons to sell disinfectants? Dunn’s book tries to address the first question, while using his background as a scientist to rectify common misrepresentations of the life that harms us and of the life that protects us.

Dunn is an amiable guide to this microscopic underworld. A professor of applied ecology at North Carolina State University, he also serves as a professor at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. Much of the information in the book comes from Dunn’s own research. But Never Home Alone is also a story about “citizen science,” as thousands of people around the world have sent in samples of dust, dirt and gunk from around their homes for laboratory analysis.

Dunn relates the scientifically accurate story1 of all these bugs as if sitting at the Thanksgiving table discussing what’s going on in the house with geeky yet charming humor. He makes light of the jargon scientists use, simplifying ‘high throughput’ as just a “fancy way of saying that one can do a lot.” Among other images, he found space to include a collage of showerheads from around the world. Then there is a close-up of a bearded bespectacled entomologist with a search light strapped to his head crouching in a corner of a carpeted room with tiny forceps hunting for insects. Sprinkled with personal stories and candid photographs of scientists ‘on the job,’ Dunn creates a rapport with readers, inviting them along for an up-close look at the personal side of the scientific work.

Dunn began his scientific career as an undergraduate studying biodiversity in the rain forests of Costa Rica, but he now works closer to home — literally. His team searches for lifeforms hiding in the domestic environmental niches of our everyday lives. Our kitchens. Our beds. Our foods. Our bodies. Our pets.

Never Home Alone explores this “indoor wilderness.” Dunn and his team have found nearly 200,000 species sharing our homes with us. Even in outer space, in the thoroughly disinfected International Space Station, there are bacteria associated with stinky feet, smelly armpits and, well, poop. One common theme through his account is how we humans are waging war against all that lives around us: the good, the bad and the ugly. We tend to ignore the good and lump the seemingly ugly with the bad.

How can the slimy gunk in our showerheads be good? Through his own research and that of many others, Dunn shows us the beauty in our “jungle of everyday life.” The gunk in our showerheads, for example, is mostly the ‘good’ bacteria that crowd out the ‘bad,’ such as the disease-causing Mycobacteria, which need to fight the gunk for space and food. The more we ‘clean’ our water with chlorine and other biocides, the more “good” gunk we kill. Meanwhile, the dangerous Mycobacterial species are free to evolve forms that are tolerant of chlorine, thriving in the absence of competition from our good gunk. In the name of cleanliness, Dunn says, “We are accelerating the rate of evolution in our homes at our own expense.”

Dunn points out that the “problem with cockroaches is us.” Our fight against cockroaches stands in for all of the “chemical wars” we are losing to pests, parasites and pathogens. “The battles are not evenly pitched,” he notes, alluding to the incredible ability of even simple creatures around us to adapt. Some strains of cockroaches have now evolved to hate glucose in order to avoid pesticide-laced treats we humans put out to exterminate them, and bacteria can evolve drug resistance at an alarming rate (as fast as 11 days) to survive our antibiotics. In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention alerted in their report, “Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States” that each year at “least 2 million people get an antibiotic-resistant infection, and at least 23,000 people die.”

As in his four previous books, Dunn strives to celebrate the importance of the extraordinary life forms we ignore just because they are invisible. Consider your laptop, on which you might be reading this. It seems sleek and aseptic, but it teems with life that includes dust mites, bacteria associated with our skin and armpits, and even rotting food. Dunn, without being pedantic, reminds us how the critters living in our dust are important. How playing outdoors with plants and butterflies is important. How growing up with “dirty-fingered siblings” is important. He warns that “the problem is not what is present but instead what is absent.”

By shutting ourselves in our disinfected air-conditioned apartments away from the germs, we have also banished ourselves from the biodiversity we need. The increased incidence of chronic inflammatory diseases, allergies and asthma seen in urbanized regions is not because we aren’t killing enough germs. It is because we are not interacting enough with the life around us. It is important to bring this microscopic, yet enormous population back into our lives. The more biodiversity we encounter, the more likely we are to encounter beneficial allies. Dunn encourages us to plant a garden, go play with butterflies. “Play the ecological lottery more times and you better your chances of getting it right,” he writes.

Despite a slow start and the occasional mire of scientific names, Never Home Alone ultimately infects you with Dunn’s curiosity about the life around us. My initial passive reading of the catalogue of microbes surrounding me quickly turned into an active search for life in my Lysol-cleaned air-conditioned apartment. It was terrifying to imagine cockroaches, fungi, bacteria, and viruses lurking on and under each surface. I found exactly one silverfish. At first I felt relieved. But the book eventually led me to the realization that finding only a single silverfish might be more terrifying. We (and I) are so skilled at killing all the living things around us that we inadvertently breed master resistant species while eliminating the good biodiversity protecting us.

As grim as this scenario sounds, Dunn proposes a simple solution: moderation. Instead of anti-microbial disinfectants, wash your hands with soap and water. Cultivate friendly bacteria by preparing fermented foods, or baking sourdough bread. Instead of trying to kill every form of life that lives with us, we must try to foster the ‘good’ microbes and weed out the ones that harm us.

1 For a fun read, do not dismiss the footnotes. They are not just citations to validate the claims made but are peppered with fascinating anecdotes.

Tanvi Butola is a neuroscience researcher at New York University Medical Center. Though still petrified of cockroaches, crickets and anything with more than four legs, she now considers finding a spider in her apartment a good omen. She spends her free time walking around in Central Park, and more recently in convenience stores looking for anti-bacterial-free cleaning agents.